- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Artisanal Work Series: Leather in Ancient Peru "Tradition and Transformation"

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: Katerine Albornoz

By Katerine Albornoz

In 2021, I had the opportunity to attend the Ruraq Maki fair, held at the Ministry of Culture of Peru, where a wide range of artisanal products from various regions of the country were exhibited. These products demonstrated a high level of craftsmanship, reflecting the significant skills of Peruvian artisans. Among the diversity of items presented, a leather purse decorated with embossed designs of flowers particularly caught my attention. This object aroused in me a deep curiosity about the techniques used by the craftsman to achieve such finishes.

This interest led me to research the tradition of leather work, aware that it is not a work exclusive to the modern era, but, rather, has deep roots in pre-Hispanic societies. In this context, this note seeks to concisely address the presence of leather work and its different existing branches, and then focus on the art of decorating leather. This approach will allow us to appreciate the continuity and evolution of this artisanal practice from ancestral times to the present day.

First, we need to address the following questions.

How is leather different from hide?

Before proceeding, it is essential to address a fundamental question about the terminology used. According to dictionaries, the hide is the external tissue that covers the body of vertebrate animals and consists of three overlapping layers: epidermis, dermis and hypodermis. In contrast, leather is obtained through a chemical process known as tanning, to which animal hide is subjected.

What does tanning consist in?

Tanning is the process by which raw hide is transformed into a durable and time-resistant material. This procedure not only preserves the hide, but also gives it essential properties such as flexibility, resistance and aesthetic appeal. In order to carry out this process, it is necessary to have a detailed knowledge of the types of hides and the appropriate tanning substances (Mayta H, 2011).

A glance at the Past: The use of leather

To better understand the long history of leather work, it is necessary to highlight that this activity is deeply linked to the geographical context in which it has developed.

Early evidence of leather work dates back to more than 100,000 years ago in Europe, where the first humans, being hunters and gatherers, led a nomadic lifestyle based on the exploitation of available natural resources. Relying mainly on animal hunting, these early humans began to put the hide of recently dead animals to practical use, observing that contact with it provided them with warmth (Meseldzic, 1998; Spangenberg et al., 2010). This observation marked the beginning of a long tradition of leather processing and use, a practice that not only provided them with protection against inclement weather, but also progressively became refined and perfected over time, becoming an essential element in various cultures over the centuries in Europe (Campos, n.d.).

In contrast, in South America, human presence dates back more than 20,000 years. Although there are indications of the manufacture of leather objects during this time, it cannot be said that it was a prevalent practice among the ancient inhabitants. This could be explained by the diversity of hunting strategies that did not focus solely on hunting large mammals, which limited the availability of, and access to pelts, (Boëda et al., 2014; Jackson et al., 2011; Marchione & Bellelli, 2013). A relevant aspect to discuss the existence and prevalence of leather work is the archaeological evidence and research that can support this activity during that period, which is limited.

Although information on this subject is scarce in South America, in the case of Peru we have some evidence that allows us to talk about leather work through archaeological records. The oldest evidence found is a hide discovered in the "Tres Ventanas" cave, located near the Chilca River, dating back approximately 8,000 years ago. Our understanding of this practice is expanded by other evidence, such as the hides of camelids and sea lions found at the Paloma site, in Lomas de Chilca, dating back to between 7,500 and 6,000 years ago (Meseldzic, 1998).

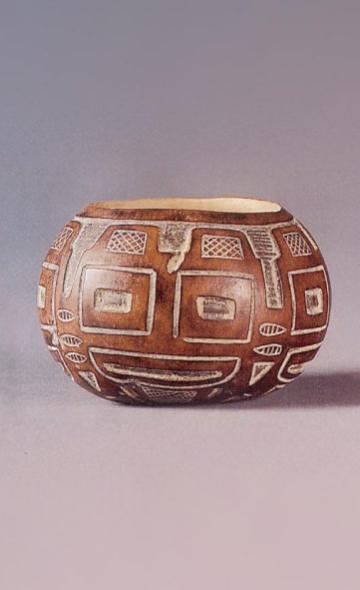

In the following years, there was a notable increase in agricultural activity, which led to significant progress and, consequently, the emergence of the textile industry around 5000 BC (Dillehay et al., n.d.). The domestication of cotton, according to Bird (1985), was a crucial milestone that drove progress, as it became the main material for the manufacture of garments and textile objects. This change displaced the use of hides and leather in the manufacture of clothing, which possibly contributed to the scarcity of remains of hides and leather from the pre-Hispanic cultural periods in the last 2000 years or so. Despite this, the use of hides and leather did not disappear completely, but, rather, was adapted, for example, to the manufacture of sandals, helmets, headdresses and musical instruments such as drums (see image 1) (Falcón & Martínez, 2009; Lavalle & Lang, 1980).

Based on the available data, it has been confirmed that pre-Hispanic cultures used various hides, such as those of sea lions, camelids, felines and rodents such as the vizcacha, among others. These hides could come from both terrestrial and aquatic animals.

How did they make hide-based objects?

The first step is to obtain the raw hide. At first, humans used their nails and fingers for this task. This natural method of acquiring hide marked the first stage in the technology of working with hides, later known as skinning or flaying. This process implies the use of stone, bone, or wooden tools.

The next step is the conservation of the hide to prevent it from rotting before tanning. To conserve the hide, one of the methods is to dehydrate it, as moisture can ruin it. One effective way to achieve this is to place the hide in the shade to dry slowly, protected from direct exposure to the sun or intense heat, which could harden it. Another form of conservation is to treat the hides with disinfectants or preservatives. Among some disinfectants that the ancient Peruvians knew of are mercury, salt, saltpeter, smoke. It is also possible to use products of vegetable and animal origin, such as resin from the molle (Peruvian pepper) tree or urine (Table 1) (Miranda, 2006).

First, several preparatory stages were carried out with the raw hide, including cleaning, soaking, washing and removing adhered flesh remains. After these prior steps, the tanning itself was carried out to transform the hide into leather. It is worth mentioning that in cases where a hairless leather was required, such as for the manufacture of sandals or other objects, after removing the flesh remains, an additional process was applied to also remove the fur from the hide, known as lime bath or hair-removal. Therefore, the specific stages varied depending on the final use that would be given to the tanned leather (Melgar, 2000; Meseldzic, 1998).

After completing the tanning process, a non-perishable, dry and rigid product is obtained. At this point, it is necessary to carry out the final finishing, which implies some additional processes. This requires greasing, which can be done with collagen resulting from the tanning process or collagen from other animals, such as seals (Table 2). This will confer to the finished product the desired softness, elasticity and waterproofness.

Once the desired material has been obtained, the garments are made, including footwear, headdresses and caps, dresses, bags and ornaments, or musical instruments, funerary implements, or others, can be made (see image 2).

From the pre-Hispanic to the Colonial: What changed?

The arrival of the Spaniards in America brought with it significant changes and introductions, among which, the introduction of animals such as cattle and sheep, which drove the development of livestock and, therefore, leather work (Assadourian, 1982; Esquivel, 1996). The manufacture of leather goods was a skill that the Spanish refined and improved over time. Throughout their history, they adopted and combined various techniques, among which stood out the Arab contributions. This merging of methods led them to develop a remarkable dexterity in this trade (Miranda, 2006; Schmitz, 1927).

At first, the conquistadors transported leather and other materials to Spain and these returned as finished products such as shoes and chairs, among others. Only in exceptional cases were the colonies allowed to tan leather, which limited this activity in the region (Miranda, 2006).

After the Spaniards settled, the leather artisans arrived, bringing with them their own tools and methods. Also, they introduced techniques such as saddlery and leathercraft. These artisans successfully established themselves in several localities, creating leather production centers. One of these centers was located in the city of Huamanga, Ayacucho, while others were in places such as Arequipa, Trujillo, and Cajamarca (Miranda, 2006).

Leather handicrafts in colonial times

During the colonial epoch, saddlery focused on the manufacture of horseback riding items, as the means of transportation of that epoch were very different from present ones, and these products were essential to the daily lives of people at that time (Enríquez & Sarzosa, 2018).

Another specialty that was also introduced was leather goods manufacturing, an artisanal trade that implies the production of cases, purses, wallets and trunks, among other objects (see image 3) (Esquivel, 1996). Furthermore, leatherworking refers to the art of ornamenting leather employing various techniques such as embossing, openwork, incision, and stamping, among others.

Returning to the present

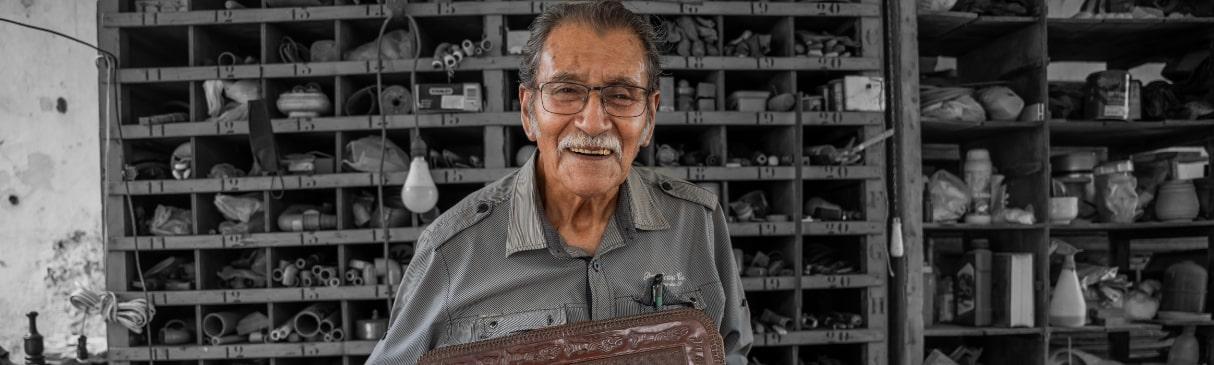

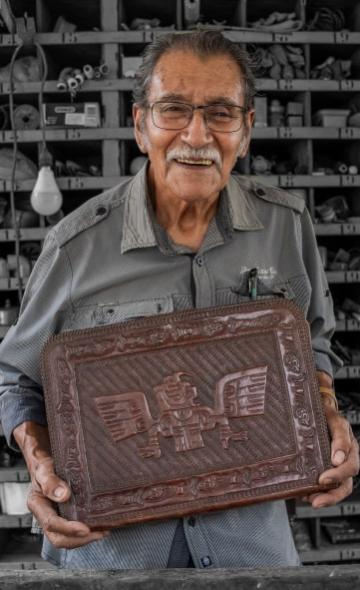

To learn more about this work at present, we have contacted Segundo Chacón Briones, from Celendín, Cajamarca, who has experience in this art.

KA: How did your interest in artisanal work begin?

SC: "Let me tell you how I discovered my passion for art. Coming from Celendín, I used to live in the San Cayetano neighborhood, on Dos de Mayo Street. The lower part of this street began with the Adventist church of Celendín. From my house to the church, there was a descent of clay soil. I would watch with curiosity how the horses left tracks when they came down with products to be sold. This sparked my interest in clay. I experimented by modeling figures, from toys to household utensils. I consulted my teacher, Alfonso Rojas, about how to burn my creations. He advised me to use cow dung as fuel. Thus, I became a toy supplier to my classmates and I also knitted hats with my cousin Dolores at night. I used to knit hats with her, under the light of a lamp or a kerosene burner, as we had no electric light. It all started out of curiosity and the need to help at home. Necessity led me to create."

KA: How did you venture into leather work?

SC: "When I arrived in Cajamarca, I was looking for a job. On the square, I met someone from my town who encouraged me to apply to university. I managed to be admitted, but then I faced a new challenge: How to sustain myself in Cajamarca? A friend told me that the university dining room needed staff, so I decided to apply and ended up working there for the five years that my studies lasted.

At the same time, I learned about an artisan center in Cajamarca that offered courses in ceramics, leather work, goldsmithing and more. I quickly enrolled in the ceramics and leather work courses. In the latter course, I learned how to make leather objects, such as coin purses and wallets, and how to decorate them. We used to buy the leather, already tanned, on Lima Street in Cajamarca."

Final Thoughts

Leather work is a practice that dates back to the beginnings of human civilization. Originally, early communities probably used leather out of necessity, using it for warmth or as a versatile resource. In pre-Hispanic societies, there is evidence of knowledge about leather tanning and its use, although information on the specific techniques of leather work in those times is scarce and poorly documented in detailed historical sources.

With the arrival of the Spaniards, the documentation on the use of leather increased, which gives us a clearer vision of the practices of our ancestors. During the colonial period, indigenous artisans adopted and adapted the new European techniques of leatherworking to their own social and cultural context. These artisans not only assimilated these practices, but they also reinterpreted them and integrated them into their own vision of the world, keeping these traditions alive to this day.

Understanding the provenance and evolution of this knowledge makes us aware of our rich cultural heritage. The permanence of these techniques at present depends not only on their historical value, but also on how we decide to integrate and preserve them in our contemporary world.

Bibliography

Assadourian, C. S. (1982). The system of the colonial economy (First). Institute of Peruvian Studies.

Bird, J. B. (1985). The preceramic excavations at The Huaca Prieta Chicama Valley, Peru (J. Hyslop & M. Dimitrijevic Skinner, Eds.; Vol. 62).

Boëda, E., Clemente-Conte, I., Fontugne, M., Lahaye, C., Pino, M., Felice, G. D., Guidon, N., Hoeltz, S., Lourdeau, A., Pagli, M., Pessis, A.-M., Viana, S., Da Costa, A., & Douville, E. (2014). A new late Pleistocene archaeological sequence in South America: the Vale da Pedra Furada (Piauí, Brazil). Antiquity, 88(341), 927–941. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00050845

Campos, J. (n.d.). The history of hide, tanning, its processes, products and footwear. International Chemical Journal for Tanning. Retrieved June 2, 2024, from https://www.quimicainternacional.com/biblioteca/historia/

Dillehay, T. D., Bonavia, D., Goodbred, S., Pino, M., Vasquez, V., Tham, T. R., Conklin, W., Splitstoser, J., Piperno, D., Iriarte, J., Grobman, A., Levi-Lazzaris, G., Moreira, D., Lopéz, M., Tung, T., Titelbaum, A., Verano, J., Adovasio, J., Cummings, L. S., … Franco, T. (n.d.). Chronology, mound-building and environment at Huaca Prieta, coastal Peru, from 13 700 to 4000 years ago. http://antiquity.ac.uk/ant/086/ant0860048.htm

Enríquez, S., & Sarzosa, J. (2018). Saddlery in the community of Zuleta, Ibarra - Ecuador [Thesis]. Universidad Técnica del Norte.

Esquivel, A. (1996). Leather Arts and Crafts in Samayac. Center for Folkloric Studies, 213–244.

Falcón, V., & Martínez, R. (2009). A painted leather drum from the National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and History of Peru. Annals of the Museum of America, 16, 9–28.

Jackson, D., Méndez, C., Núñez, L., & Jackson, D. (2011). Processing of extinct fauna during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition in north-central Chile. PUCP Archaeology Bulletin, 15, 315–336. https://doi.org/10.18800/boletindearqueologiapucp.201101.012

Lavalle, J. A. de, & Lang, W. (1980). Pre-Columbian Art: Part One Textile Art and Ornaments. Central Bank of Peru.

Marchione, P. C., & Bellelli, C. (2013). Leather work among hunter-gatherers in central-northern Patagonia. Campo Moncada 2 (Middle valley of the Chubut River). Relations of the Argentine Society of Anthropology XXXVIII, 1, 223–246.

Mayta H, J. (2011). Manual of fur trade and tannery. http://www.unap.edu.pe

Melgar, D. (2000). Leather Technology: Quality Tanning Processes and Machinery: Volume I. Center for Artisanal Development.

Meseldzic, Z. (1998). Hides and Leather of pre-Columbian Peru: Volume I (S. Antúnez de Mayolo, Ed.). Geographical Society of Lima.

Miranda, E. (2006). Some contributions for the study of leather crafts. Writing and Thought, 19, 79–98.

Schmitz, H. (1927). History of furniture (Third). Editorial Gustavo Gili.

Spangenberg, J. E., Ferrer, M., Tschudin, P., Volken, M., & Hafner, A. (2010). Microstructural, chemical and isotopic evidence for the origin of late neolithic leather recovered from an ice field in the Swiss Alps. Journal of Archaeological Science, 37(8), 1851–1865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2010.02.003

Researchers , outstanding news